Um das maiores dificuldades para os falantes de português é o uso correto dos verbos "go" e "come". O uso trocado pode causar problemas mais sérios de comunicação do que simplesmente errar uma questão na sua prova de vestibular e Enem. Para garantir que você nunca erre e cometa mal entendidos, foi desenvolvida uma técnica simples, especialmente para os brasileiros, denominada de "inversão parcial". Para você entender seu uso e treinar para a prova, vão ser descritas as etapas seguintes em inglês com ilustrações explicativas. Let's go!

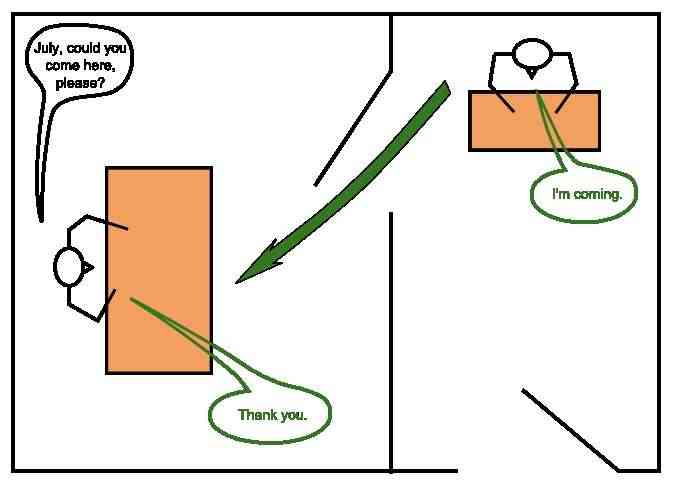

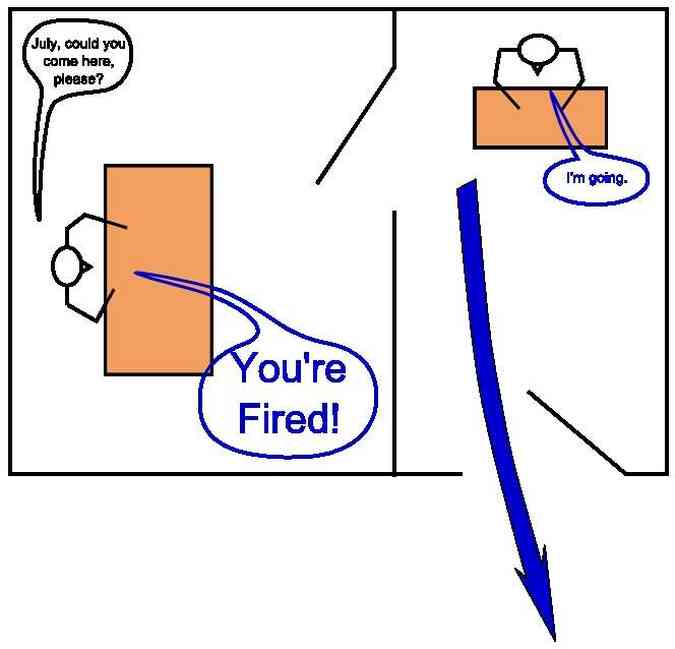

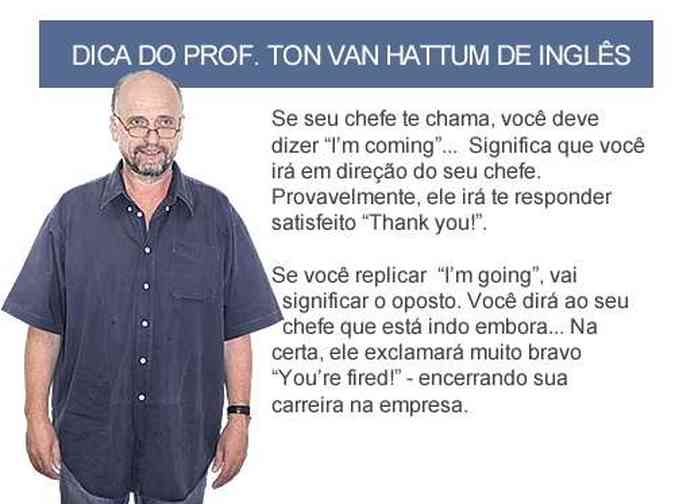

The correct use of the verbs come and go causes problems for speakers of Portuguese. Depending on the context, come and go indicate a direction opposite to the corresponding words in Portuguese. There is a partial, context dependent inversion, of the direction indicated by come and go. Correct use is shown in Figure 1. Incorrect use and possible resulting problem is shown in Figure 2.

This context dependent inversion of come and go is probably result of the fact that Portuguese has a preposition indicating “there where you, the listener, are”, while English doesn't have a preposition with this meaning. When responding to a request to come, one communicates “there where you are” by placing oneself in the place of the person who made the request. As a result, the direction indicated by come and go are inverted in these cases.

Answering “I'm coming” means “I'm moving to the place where you, who made the request, are” (See Figure 1). Answering “I'm going” means “I'm moving to a place where neither of us is” (Figure 2).

The same context dependent inversion happens with bring, which means “come and have something or somebody with oneself” and take, which means “go and have something or somebody with oneself”.

Not applying this context dependent inversion correctly in English, causes that a person who makes a request thinks the request is refused. This can lead to unpleasant situations, like in Figure 2.

The idea of placing oneself in the situation of the other also helps to find out which word to use when referring to a place where none of the speakers is at the time of requesting or suggesting. This can happen for instance when making an appointment and deciding where to meet.

Both of the following ways of suggesting are possible but there is a small difference in connotation.

- Yesterday I met Julie. She wants to go to the open-air museum. Do you want to go with us?

Explanation: We all move in the same direction. - Yesterday I met Julie. She wants to go to the open-air museum. Do you want to come with us?

Explanation: We go and take you with us. - Let's meet in the afternoon at Julie's. I'll meet her at lunch. When do you think you can come?

Explanation: In the afternoon, “I” and Julie are already there so at that time “you” will be moving in “my” direction. That is why the word come is used.

The problem of mixing up come and go, can be avoided by using alternatives like the following.

- “When do you think you can arrive.”

- “When do you think you will be there.”

They are common expressions for situations like this.

Ton van Hattum é professor de Inglês do Percurso Pré-vestibular e Enem.

Fonte: https://tonvanhattum.com.br/material/ComeGo-partial_inversion.html